History

A short history of Falcon Rest Mansion ...

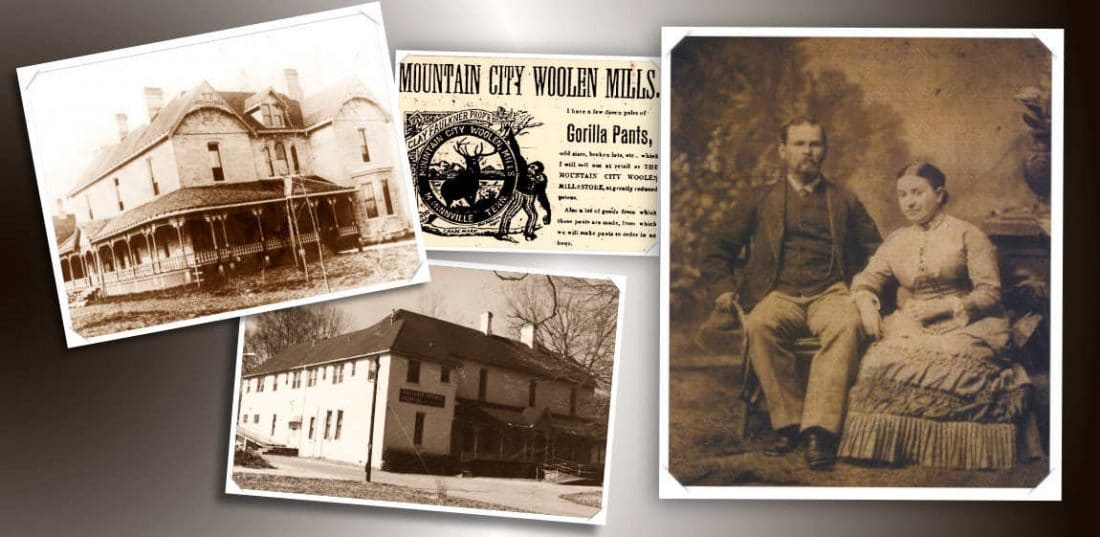

In 1896, entrepreneur Clay Faulkner told his wife Mary he’d build her “the grandest mansion in Tennessee” if she would move next to their woolen mill, 2-1/2 miles from downtown McMinnville.

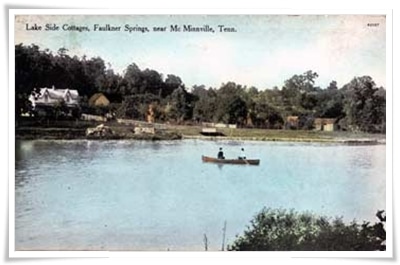

Mary agreed, and Faulkner supervised construction as enthusiastically as he promoted the mill’s “Gorilla Pants” (so strong even a gorilla couldn’t tear them apart) and mineral water at the Faulkner Springs Hotel, the “ideal health and pleasure resort” he would eventually open on the lake across the road.

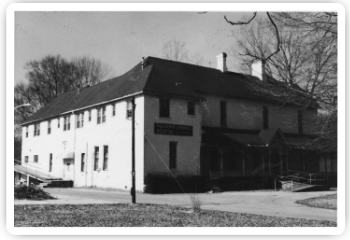

In the 1940s, Clay Faulkner’s mansion was converted into a hospital and nursing home. An early ad boasted a quiet location and an ideal climate, at rates of $5.00 to 8.00 per day — according to care required. By the mid-1950’s, Dr. J.P. Dietrich had added onto the building and renamed it the Faulkner Springs Hospital. Local folks still tell fond stories about the doctor and the house where he dispensed medicine and love. The doctor closed the hospital in 1968. He stripped out much of the woodwork in an unsuccessful attempt to tear down the solid brick structure, then let it sit empty for a decade an a half.

When George McGlothin bought the old house at auction in 1989, it was a ghost of its former glory. He and his wife Charlien began four years of restoration, tackling 95 percent of the work themselves. Their efforts were rewarded with the National Trust’s Great American Home Award for restoration in 1997.

By mid-2017, the McGlothins had owned Falcon Rest longer than anyone else in its history. As of 2023, they have had it open to the public as a historic attraction for 30 years. They are still dedicated to making the property and the visitor experience better all the time.

Want to know more?

Read Falcon Rest's National Register application below for details ...

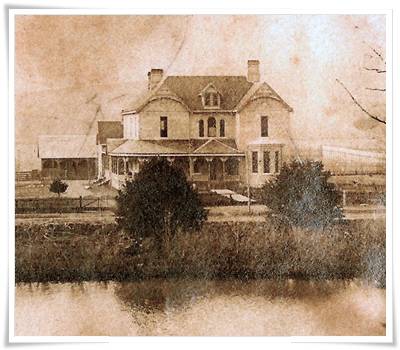

Clay Faulkner – a leading Warren County, Tenn., manufacturer in the late 1800s – built a gracious Victorian residence for his wife and five children in 1896-97. The 10,000- square-foot Queen Anne mansion was located on a 144-acre tract just south of Faulkner’s Mountain City Woolen Mill, two-and-a-half miles from McMinnville. Only five acres of the original 144 remain with the property, but the level corner lot with many towering trees forms an elegant setting for the Victorian mansion.

Mr. Faulkner’s mansion is the most outstanding example of late Victorian architecture remaining in the county. And it was built by a man whose family heritage and life’s work centered around water-driven mills, the foundation of the county’s 19th-century economy.

Warren County Mills and Faulkners

The doctor, though, followed Andrew Jackson to war, and the educator moved to the new town of McMinnville. But manufacturer Henry Briddleman remained, and in 1812 he founded a cotton factory on “Charley” Creek.

Asa Faulkner, Clay’s father, worked for Briddleman as a lad, and in 1846 he purchased the mill. Asa eventually established the Annis Cotton Mill and a flouring mill, both on the Barren Fork of the Collins River near downtown McMinnville. A newspaper article shortly before his death in 1886 called Asa “the nestor of all Warren County’s manufacturing interests.”

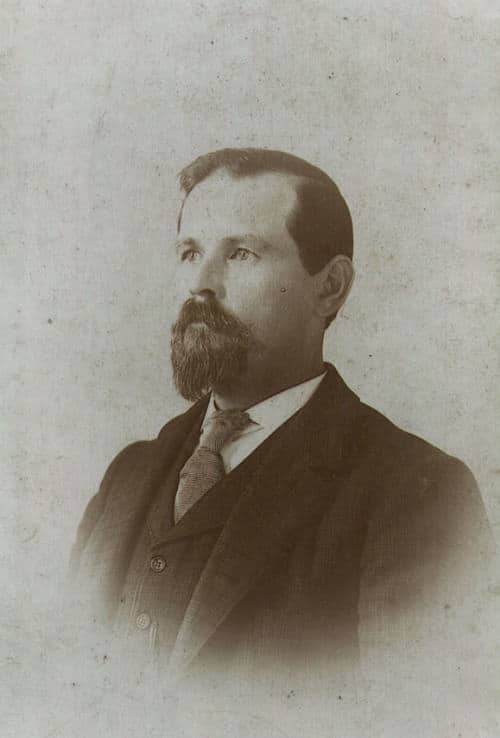

Clay Faulkner and Commerce

More than any of Asa’s 19 children, Clay carried on his father’s tradition of commerce. Born in 1845, Clay was academically educated in New York and trained as a machinist. The 1870 census lists him as a farmer, but his milling career had actually begun four years earlier. In 1866, the 21-year-old Clay and his brother J.J. took charge of the Butler Flouring Mills on Charles Creek in Warren County.

The mill that would become Clay’s primary focus — also on Charles Creek — came into the possession of Clay and his older brother T.H. in 1873. That was the same year Clay married Mary King Sanders of Carthage, Tenn. Clay and T.H. installed new machinery to upgrade the capacity of the facility, then known as Faulkner Woolen Mills.

By 1877, Clay and T.H., along with the latter’s father-in-law Judge Robert Cantrell, were running both Asa’s original mill and the new one. Both partnerships were dissolved two years later, with T.H. and Cantrell taking possession of Asa’s mill and Clay becoming sole owner of the other.

The 1880 census shows that Clay’s mill, which he renamed Mountain City Woolen Mills, had $20,000 capital invested and employed 18 people. Supplies and products on hand were worth a total of $43,000. Clay upgraded the machinery again in 1887. The mill had an annual capacity of 150,000 yards of cloth. Clay Faulkner also owned a sawmill on Caney Fork River.

Perhaps Clay’s most ambitious venture was the Falls City Cotton Mill, also known as the Great Falls Cotton Mill. It began in 1883 as a dream of his father Asa — then 81 years old — who purchased the land between the Collins River and the Caney Fork at the Great Falls of Rock Island, Tenn. Asa and Clay, along with Jesse and H.L. Walling, established the Great Falls Manufacturing Company. The group had a wheel pit dug and a low diversion dam built at the falls.

The elder Faulkner died in 1886, but the surviving partners went on with the work. The Falls City Cotton Mill was chartered in 1892 with a capital investment of $30,000 “to manufacture, spin, weave, bleach, dye, print, finish and sell all goods of every kind made from wool and cotton.” Clay in all probability oversaw the construction of the three-story mill structure (listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983). At that time, Faulkner, a devout church-goer, was chairman of the building committee for the McMinnville Methodist Episcopal Church. Church records state that, while the bricks were being made for the mill, Clay had enough made to construct the new church building as well.

The Falls City Cotton Mill became well known for its sheeting, which Clay’s granddaughter says he sold to the United States government during “the war” (doubtless the Spanish-American War). Newspaper accounts do show Clay making frequent trips to Washington during the late 1890s, so that may have been their purpose.

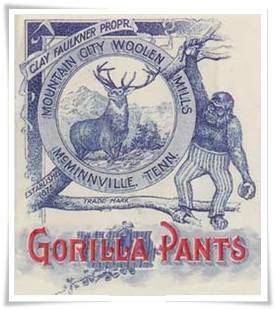

Faulkner’s flair for advertising (and perhaps his sense of humor) was reflected in the name he chose for the jeans he manufactured: Gorilla Pants. They were, he affirmed, so strong even a gorilla could not tear them apart! The slogan was, “Gorilla grip. They never rip!”

An 1896 article in the Southern Standard newspaper reported, “The Mountain City Woolen Mills is one of the best equipped and best managed manufacturing plants in the state, and its product of Jeans and Gorilla Pants are growing in popular favor and demand.”

Faulkner provided housing for his mill hands, and a later article referred to the area around the mill as “a flourishing hamlet.” In addition to the dam which powered the mill, Faulkner had a blacksmith shop, a farm which furnished fresh produce, meat and dairy products for family and workers, and an “outlet store” where local residents could purchase his products. Faulkner, the trained machinist and born innovator, built a reservoir that provided water to the mill and surrounding houses for everyday use as well as fire protection. The reservoir was used by area residents well into the 20th century. Ever one to improve on the status quo, he invented a rolling axle and obtained several patents for it. He almost sold the idea to Studebaker, but they decided to manufacture automobiles instead of wagons!

Flood Leads to a New Career

Clay Faulkner was at work in his beloved Mountain City Woolen Mills when a torrential rainstorm signaled the beginning of the end of the dominance of water-powered mills over the economy of Warren County.

It was Good Friday in 1902, and the deluge sent “death and destruction in its wake.” Faulkner and his hands were trapped in the mill for hours by the raging waters, and one worker there lost his life trying to escape.

When the water subsided, Asa’s original factory, the Tennessee Woolen Mills, had suffered $25,000 damage. The Annis Cotton Mill was virtually destroyed. The wheel house at the Falls City Cotton Mill was washed away. The Falcon Flouring mill, owned by “Messrs. Faulkner and Walling” had been pushed off its foundation. Ironically, the Mountain City Woolen Mill buildings were not impacted as heavily. The newspaper account notes that “the dam was damaged to some extent and injury to goods and machinery will foot several thousand dollars.” Homes along the creek also suffered, although Clay’s was untouched. One nearby house was washed away and four residents drowned.

Faulkner’s descendants have a document he signed years before with his father guaranteeing the property of people along the creek from damage caused by his dam.

Those relatives say that the flood cost Clay dearly, but he lived up to his obligations and reimbursed his neighbors. Of the 32 water-powered mills operating in Warren County in 1895, less than a dozen survived the 1902 disaster.

It was only after the flood that Faulkner found time to pursue another business interest — the search for medicinal spring water on his property. A first-person account in a 1906 advertising booklet asserts that, since 1896, Faulkner had been in “wretched health” after 15 years of kidney and bladder troubles. He “traversed the country in search of health” to no avail, until in 1897 an employee called his attention to mineral water in springs on his own property. Faulkner claimed (perhaps showing a trace of his flair for salesmanship) that from constant use of the mineral water, he “gradually grew better, until his kidneys were in perfect condition.” The rush of business delayed a search for the source of the water, but in the early 1900s he took it up in earnest. A total of four types of spring water “of medicinal value” were discovered on the property. By 1906, Faulkner was shipping mineral water by rail from McMinnville at $4 a barrel.

To the enterprising Faulkner, the next logical step was to construct a resort hotel on his property, since “mineral water gives much better and quicker results when used fresh from the spring.”

In 1906, he closed the mill and remodeled the building with verandas all around, on the artificial lake formed by his dam. He gave his own name to the business, calling it the “Faulkner Springs Hotel,” and to this day the community is still known as Faulkner Springs. The hotel became a popular resort, frequented by the wealthy from Nashville and surrounding areas. The advertising brochure, along with local memories, paints an idyllic picture of rowing on the lake, hikes along the creek, and festive dances in the ballroom. Perhaps the early dream of a utopia on the Charles Creek came very near to reality.

In 1906, he closed the mill and remodeled the building with verandas all around, on the artificial lake formed by his dam. He gave his own name to the business, calling it the “Faulkner Springs Hotel,” and to this day the community is still known as Faulkner Springs. The hotel became a popular resort, frequented by the wealthy from Nashville and surrounding areas. The advertising brochure, along with local memories, paints an idyllic picture of rowing on the lake, hikes along the creek, and festive dances in the ballroom. Perhaps the early dream of a utopia on the Charles Creek came very near to reality.

The Faulkners' Falcon Rest Mansion

By the time he reached his 50s, Clay Faulkner had grown tired of the two-and-a-half-mile buggy ride from his house in town to the mill. Perhaps his kidney ailment contributed to his discomfort. At any rate, he promised his wife Mary (a cultured lady, according to a local historian of the era) that if she would move to the country near the mill, he would build her “the grandest mansion in Tennessee.” The careful attention to detail, the tasteful elegance, the top-notch materials, and the quality of workmanship in “Falcon Rest” testify that he was a man of his word.

The April 4, 1896, the Southern Standard reported that Faulkner had purchased the farm adjoining his mill from brother T.H.’s widow to build “a large and handsome dwelling house” for his family. Faulkner closely supervised construction. It is said he told workmen to dig down to the bedrock before they started laying the foundation. (In the 1980s, the previous owner excavated eight feet next to one wall, and still did not reach its bottom.) Because the interior walls, as well as the exterior, are solid brick, every wall in the house rests on this solid bedrock foundation. Even though the house was virtually abandoned for 15 years from the late 1960s to early 1980s, the walls seem to be as plumb today as they were over 100 years ago.

Clay carefully inspected everything that went into the house to make sure it was of the highest quality. One of the men who eventually witnessed Clay’s will told this story: Workmen were installing the tongue-and-groove boards in the veranda ceiling one day when Faulkner went into town on an errand. When he came back, he found that a board they had installed an hour before had a tiny knothole in it. Even though the carpenters protested that the hole would not show after painting, Faulkner had them remove the whole hour’s work, since he would not allow any materials of inferior quality in his home.

This meticulous construction took time. It was almost a year to the day after the newspaper reported Clay’s purchase of the property, that an article noted Clay and his family had moved into their new home on the previous Saturday (March 28, 1897).

In choosing materials and design elements, Faulkner selected graceful details which reflected a refined elegance, while avoiding the gaudy ornateness sometimes seen in 1890s construction. The curved windows at the front of the house, gingerbread veranda, brickwork detailing, and attic vents added to the overall richness of the structure without shouting for attention. The brass door hardware, the marble surrounds on the fireplaces, gracious staircase, intricately carved woodwork, and striking spindle frieze in the parlor were obviously the best that money could buy. Local workers who laid the hardwood floors – kept polished to a bright shine during Faulkner’s time – were paid a dollar a day. But the carpenters Clay brought in from Nashville to build the staircase and decorative woodwork commanded ten times those wages!

Elegance, however, did not overshadow efficiency. The mansion is situated so that, even on the hottest days, there blows a cool breeze over its inviting north-and east-facing verandas. The elaborate waterworks system piped in from the spring provided refrigeration for perishables, fresh water for cooking and bathing, and cooled the building. Summer comfort was enhanced with 12-foot ceilings and cross ventilation in virtually every room.

Electrification may have come to most of rural Tennessee in the 1930s, but Clay’s house was lit with electric lights. Indeed, street lights even lined the road between the mill and the mansion and eventually illuminated the lake across the road at the hotel. Not restricted to the one-sided heat of coal-burning fireplaces, the family was warmed by a central steam heating system during winter months. The large kitchen, pantry and spring house provided ample room to prepare and store food not only for the family but for farmhands and servants as well.

Indeed, the Standard attested that Faulkner’s house had “all the improvements and conveniences of a model city dwelling.”

The Mansion in Later Years

Clay Faulkner died in 1916. Three years later Mary moved to Nashville and sold Falcon Rest a local contractor named George Beech. In 1929, the mansion was purchased by Dr. Herman Reynolds. He began its long association with the medical community. Dr. Reynolds, who practiced both medicine and dentistry, had a clinic in his home there until his death in 1941.

W.V. Jones, later mayor of McMinnville, purchased the house in 1943 and used it as his private residence for two years. Subsequent owners were H.R. Stewart, Cumberland Valley Sanitarium, Inc., Louella Doub, Cumberland Conference of Seventh Day Adventists, and Faulkner Springs Sanitarium and Hospital (Dr. J.P. Dietrich). Almost constantly between the time Mr. Stewart bought the house and the Faulkner Springs Hospital was closed in 1968, it was a nursing home (or sanitarium) for the elderly and, for its day, a well-equipped hospital. Hundreds of babies were born there over the years, and almost everyone in town has a fond story to tell about experiences at the beloved hospital.

Progress overtook the Faulkner Springs facility when a new, modern hospital was built in McMinnville. In 1968, Dr. Dietrich gave away the beds, then closed the doors without disturbing anything else. Except for the doctor’s abortive attempt to tear it down, the house sat vacant – a ghost of its past glory – until Joe Grissom purchased it in 1983. Grissom and his wife began the laborious task of clearing out the hospital clutter and putting the house back together — all the way to reconstructing the staircase. They had restored three rooms when the house was bought by its present owners, George and Charlien McGlothin, in 1989.

Read the original 1992 National Register of Historic Places application on the National Park Service website: Clay Faulkner Home.